I’ve been reading books in Portuguese at church lately and found some gems! Will post some here.

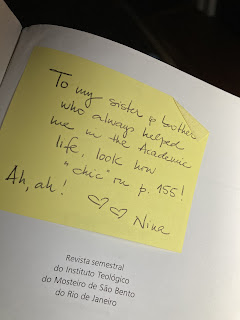

This is a theological journal from St Benedict Abbey in Rio where Sr Martina taught for a few years. This issue has an article by her about St Edith Stein. Sister wrote a dedication. Translation below.

Edith Stein: like gold purified by fire

By Prof Marta Braga

No scholar of contemporary Philosophy, Theology and even History can ignore the great impact and great meaning of the life and thought of St. Edith Stein - or St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, if we take her religious name. In fact, hers was one of the great personalities of our times. We will talk here a little about his biographical aspects, which explain and substantiate, of course, much of her thinking, and they also certainly deserve our attention and admiration. Edith Stein's life was not very long, but it was dense. I propose to accompany her life and narrate it briefly, focusing on the facts.

They speak for themselves, without, in my opinion, the immediate need for interpretation, about the drama and greatness of this soul.

The youngest of the eleven children of Siegrid Stein and Auguste Courant, Edith was born on October 12, 1891 in the then German city of Breslau, now Wroclaw, Poland. The family was of Jewish faith, practicing and Orthodox. Edith's birthday coincided with Yom Kippur's party, which was considered a good predestination for the child's destiny.

Her father passed away before the girl turned two years old. The mother, a very strong personality who would leave a deep mark on her children, began to bear all the care of the family, including her husband's important wood business, which became very successful. Supported by the maternal strength of this Woman, who was also deeply religious, the children were able to build for themselves an emotionally stable life, pious and full of great cultural interests and a great sense of family unity. The Stein family, although Jewish, was not distinguished externally from the other German families in its environment, but perhaps by the considered social position and the practice of charity: it was customary among them, coss tume encouraged by the mother, to help friends in need, to delay the collection of payments, to give with abundance on the occasion of religious festivals.

By Prof Marta Braga

No scholar of contemporary Philosophy, Theology and even History can ignore the great impact and great meaning of the life and thought of St. Edith Stein - or St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, if we take her religious name. In fact, hers was one of the great personalities of our times. We will talk here a little about his biographical aspects, which explain and substantiate, of course, much of her thinking, and they also certainly deserve our attention and admiration. Edith Stein's life was not very long, but it was dense. I propose to accompany her life and narrate it briefly, focusing on the facts.

They speak for themselves, without, in my opinion, the immediate need for interpretation, about the drama and greatness of this soul.

The youngest of the eleven children of Siegrid Stein and Auguste Courant, Edith was born on October 12, 1891 in the then German city of Breslau, now Wroclaw, Poland. The family was of Jewish faith, practicing and Orthodox. Edith's birthday coincided with Yom Kippur's party, which was considered a good predestination for the child's destiny.

Her father passed away before the girl turned two years old. The mother, a very strong personality who would leave a deep mark on her children, began to bear all the care of the family, including her husband's important wood business, which became very successful. Supported by the maternal strength of this Woman, who was also deeply religious, the children were able to build for themselves an emotionally stable life, pious and full of great cultural interests and a great sense of family unity. The Stein family, although Jewish, was not distinguished externally from the other German families in its environment, but perhaps by the considered social position and the practice of charity: it was customary among them, coss tume encouraged by the mother, to help friends in need, to delay the collection of payments, to give with abundance on the occasion of religious festivals.

Edith grew up very spoiled by her older siblings and they told her that she was a capricious, difficult child, but at the same time very attractive and early intelligent. Her extreme sensitivity is noted as small, especially in the independence of his character. When they put her in Kindergarten, she cried every day, until her mother decided to try to include her already in the first grade of elementary school, despite her young age. In a few months she became the first in the class, a position she retained throughout her school life, although officially she was always in second place, because of her religion.

After elementary school, Edith decided to abandon her studies, with the enthusiasm of a teenager to find some ideal that would lead her to a life of important and heroic achievements. At the same time, she devoted himself more and more deeply to individual reading. It was in this time introverted to the extreme and the prototype of a young intellectual, perhaps rationalist and individualist, although even then she did not lose her special personal charisma.

For a few months spent in Hamburg, in the house of a newly married sister, and in the midst of a lay and atheist environment, she decided to voluntarily abandon her family faith.

At her mother's insistence, she returned to Breslau and concluded, once again brilliantly, secondary education in 1910. The study became for her, from this moment on, the essence of life. Her colleagues, however, also admired her for what they describe as her extreme modesty and the total trust and authenticity that her personality conveys. The school principal used to say about her, alluding to her last name Stein = stone: “Hit the stone and wisdom will come out of it.”

Now entering adulthood, Edith was leaving her self-absorbed way and began to surround herself with a good group of friends, like her increasingly interested in Philosophy. In 1911 he entered the University of Breslau. Her mother wanted her to study Law, but in her independence Edith enrolled in the course of Language, History and Philosophy. University activities affect, at least the family direction.

The academic life then appeared as Edith's professional vocation. Advancing continuously, she began to look for advisors for a possible doctorate. She was interested initially by Professor Wilhelm Stein a decadent type, according to her, of the humanist Jew, but his area was psychology, and Edith desired Philosophy. And at this time she beginsef to read the works of Edmund Husserl, a professor at the University of Göttingen.

Edith, however, was not what can be called an academicist. Her interest in the study was in the search for knowledge, and a knowledge that, she would tell later, turned to the search for a reality and a truth that she sensed existed, in addition to the material and immediate reality.

She still accompanied his mother to the Synagogue, but definitely dod not participate in of Jewish faith. Finally, obtaining family permission, she transferred to Gottingen in 1913. Thus began a new phase of her life, a phase that would be of glory and suffering.

At the University she soon joined the large group that Husserl gathered around his recently published magazine Annals of Philosophy and Phenomenological research and that included names such as Adolf Reinech, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Max Scheler and Martin Heidegger. Edith's health was gradually shaken due to the concentration in study and a huge effort of spiritual search. She began to realize her own limitations and defects, she was no longer so sure of herself and her atheism. She faced the normal crises of her age and her environment, but she still stood out for maintaining a life of high morals and great kindness. Also in love and life she sought an ideal of truth and beauty. Studying many times from six in the morning to midnight, Edith became in a short time perhaps the best disciple of Hursserl. She reserved space however for walks and a social life that deeply rejoiced her.

It was Max Scheler who first opened her eyes to the world of Catholicism, himself newly converted. Edith began to open up and look for her human side from a not only intellectual perspective. She soon had a chance to prove this new experience. In 1914 the first world war was breaking out. Edith soon enrolled in the Red Cross, seeing this period as a necessary interruption in activities of personal interest, for the love of the homeland. In 1915 she was assigned to work in a hospital in Austria. Her mother forbade her to go, but Edith went nevertheless. During the few months she lived in this environment, her humanism was proven: in the midst of epidemics, mutilated bodies and all kinds of misery and difficulties - realities that she had never seen until then - Edith also proved to be brilliant in the science of life, spending endless hours on work, care, consolation, kindness. She would say later that this was a unique experience, which really awakened her to the reality of life.

With very weak health she returned to Götingen and was able to start her doctorate, under the guidance of the very demanding Husserl. In August 1916, in an academic world that was practically unaware of the presence of women, Stein obtained the doctorate summa cum laude after ten hours in front of the examining court. The next day, she started working as Husserl's assistant. For a year she would have a tireless and very useful work with her master.

Edith would say that in these times her search for truth was already like a prayer. Husserl himself led her to this; and the influence of the Reinach couple, converts from Judaism to Protestantism, was immense in her. When Adolf Reinach died, still in the first war, his wife spoke to Edith of the joy of the cross, and this was his first great impression of the existence of Christ. Other Catholic experiences impressed her vividly at this time, especially the testimony of personal devotions.

In 1918 Edith left the position with Husserl, to try to pursue a career of her own. At this moment, then, her own cross began. She was rejected by all Universities, for the double fact that she was Jewish and a woman. Returning to the maternal home, she began to teach in secondary institutions, also dedicating herself to publishing independent works.

In 1921, during a vacation at a friend's house, she came across a Life of Santa Teresa d'Ávila. The next day she bought a missal and a catechism and went to mass. The influence that these new readings exerted on her is overwhelming. The following year, 1922, Edith was baptized and entered the Catholic Church.

The shock for the family and, above all, for the mother, was very strong. She would never again be considered an integral part of her tradition and her home.

The pain for herself was immense at this time, mitigated only by the approach of her older sister, Rosa, who would later follow in her footsteps.

Due to the influence of St. Teresa, Edith soon thought of becoming a Carmelite, but her spiritual director, the Jesuit Joseph Schwind, advised her to dedicate herself for the time to study and teaching. It was only a year later that Edith would accept, however, a position at Speyer's Dominican College.

Edith would tell us at this time about the importance she began to attribute to the human formation of the students. This would be a happy and fruitful period for her. Her students witnessed the great example of prayer and spirit of poverty left by the teacher. She dedicated herself deeply to school life and the respect and friendship that surrounded her almost reached veneration. A student later reminded that Dr. Stein lived in a simple room, with many books on large bookshelves. There passed their disciples, the older ones, some beautiful and interesting late afternoons, literally sitting at her feet and drinking her words. The idea of dedicating oneself entirely to God increased in her. She also insisted on becoming religious but obedient to the advice of the confessor who still indicated to him the way of the world.She remained deeply dedicated to Philosophy. And it was at this time that Edith discovered St. Thomas Aquinas. On the occasion of the seventy ara that Husserl published the essay “The Phenomenology of Husserl and the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas”. In 1928 Edith would write that Saint Thomas Aquinas taught her that science can also be practiced as a service to God.

Her life was then focused on study and prayer. She read and translated Cardinal Newman's works. She went deeper and deeper into the spiritual life. We see her words in a poetry of this time:

All the plans that You prepared,

that they come to be.

And when you ask me,

in silence,

the suffering, the pain,

help me to give!

May I completely forget my poor self, so that, dead to me, only for you I live.

In 1928 her confessor died. In the next five years, Edith would entrust the Benedictines of Beuron with her spiritual guidance. They also advised her to pursue an academic career. Conferences and courses increased, their interests focused more and more on Thomism. She said in 1931 that St. Thomas was no longer satisfied with the few hours she could reserve for him: he demanded them all. She left work to focus on writing and publishing the publication of the “Controversies on Truth,” a work that came out in two volumes, in 1931 and 1932.

Also in 1932 she finally got a position as a higher education teacher at the Association of Catholic Teachers. In the same year she participated as the only woman in the Congress on Phenomenology and Tomism promoted in Paris by the Société Thomiste, in which philosophers of the time such as Maritain and Berdiaev wanted to listen to her.

Among the topics she spoke about at this time, in several lectures, was that of women. Edith Stein would be recognized as one of the great defenders of the role of women in modern society. Many women who listened to her, however, observed surprised that the figure of Edith did not at all inspire an arrogant or pretentious attitude, despite her authority and the injustices she suffered. On the contrary, they said of Edith that she was a simple and kind woman, who firmly defended that women's access to the most varied professional branches could mean a blessing for social life precisely if she were in accordance with the female way of being. Edith was then a well-known name throughout the European philosophical milieu.

In February 1933, however, all of Edith Stein's professional glory was abruptly interrupted. Hitler had assumed the post of Chancellor in January of the same year and the first anti-Jewish laws caused Edith to decide to resign from her new job, before endangering her institution by her presence. It was the beginning of her Via Dolorosa, her way of the cross. Edith walked this path in communion with the suffering of her people. She would write later that once again God had extended his hand harshly over his people, and that the fate of this people would also be his own.

Concerned about her future, the friends of the institution where he taught found her a job offer in Chile in 1933. But Edith was already determined to finally take the long-awaited step: to join Carmel.

Pope Pius XI practically bombarded Germany at the time with protest notes against Nazism. Hitler ignored them all, increasingly punishing the Jewish population. Also ignoring the Concordat with the Church, signed in 1933, he began to persecute Catholics. The situation in Germany has become critical. In 1937 Pius XI launched the encyclical Mit brennender sorge (“with ardent concern”), which managed to circumvent censorship and was read in all German parishes. The Nazi government's reprisal was clear and immense: the concentration camps were filled with priests and religious. Pius XII would later take the same path as his predecessor, being more careful, however, so that the reprisals were not so serious.

But still in August 1933, Edith went to the house and communicated her new decision to her mother and sister Rosa. The mother, in a painful situation and already very old, respected her daughter's decision but could never accept it. When they said goodbye, she said to her daughter: May the Eternal be with you. They would never see each other again and Edith would never receive any response from the letters she wrote to her mother until her death in 1936. On October 13, 1933, Edith Stein entered the Carmel of the German city of Cologne.

The nine years that Edith Stein spent in Carmelo are, of course, a more secret part of her life. In the eyes of many, the great philosopher had buried herself and ended her career in failure. Husserl commented on this occasion that if everything were not absolutely authentic in her, he would say that there was in her decision anything affected and artificial. How could a forty-two-year-old woman, of always independent life, who had reached such pinnacles of thought, adapt to manual work - for which she had no aptitude -, to the hidden routine, to obedience, to living with sisters with lower intellectual abilities, and still be happy? Edith herself would answer that she was now in the place to which she had belonged for a long time. Her adaptation seems to have been serene and immediate. Those who came to visit her, often to ask her for advice and philosophical opinions, were impressed. Edith wrote to my friend, also philosopher, Gertrud von Le Fort, who didn't imagine how much Edith was embarrassed of when they talked about her life of sacrifice. Life sacrificed was the one she had taken when she was away, she said. On April 15, 1934, Edith Stein took the Carmelite habit, becoming sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. On April 2, 1938, she made the perpetual vows.

In the same year of 1938, fearful that her presence could endanger her community in Cologne, Edith asked to be transferred to another Carmel; the superior, however, saw no need for this. In the elections of the same year, Edith was banned from voting because she was Jewish and was forced to declare it in writing. Finally on December 31, 1938 she managed to be transferred to Carmelo de Echt, in the Netherlands, where they received her with open arms, as well as her sister Rosa, who had become a member of the Carmelites third order.

Sister Teresa continued her philosophical work, still in Carmel. She learned Dutch and thus became fluent in six languages. She then began her work “The Science of the Cross.” The situation for the Jews got worse every day. Edith asked the Swiss government for a refugee pass. There was no problem and she received it, having a well-known name as he had. But sister Rosa didn't get it and Edith refused to go without her. In 1942 the so-called final solution for the Jews in the extermination camps began. Edith and Rosa finally received the Swiss passes but the occupation government in the Netherlands did not allow them to leave. Edith was forced to appear twice before the Gestapo, and in these moments her first words were always “Praised Be Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

The Dutch Church, seeing the new situation of Jews and Catholics, decided to protest publicly and vehemently. Among other measures, the bishop of Utrecht sent a hard letter to the German Nazi authorities, a letter that was published in the Netherlands. The consequent deportations practically decimated the Jews of the Netherlands and much of the Catholic religious orders, and made Pius XII abandon the idea of a clearer and more public protest.

On August 2, SS soldiers arrived at Carmel in Echt and demanded to see the two Stein sisters. Despite the superior's protests, the two followed him taking only a small travel suitcase. On the nearby streets people saw them pass by and cried, saying goodbye to the sisters. A few days before Edith had written a poem that ended like this:

Those You chose

to accompany You,

today must surround You

by the cross.

We know little about these last few days. Just some news given by well-known people who saw the two sisters, such as an old student of Edith who heard the teacher greet her by name at a train station. Edith would also write, on the way to Germany, two small notes to Echt and Switzerland. The prisoners thought they would be taken to forced labor in the east. But Edith seemed to sense the truth. One of the latest news about her comes from a woman who managed to survive the war and who said that the big difference between Edith Stein and the other sisters was in her silence, and that when she imagined her, sitting in the tent, her figure still awakened in her a thought: “a pietà without the Christ.”

According to later investigations, the two sisters were taken to the gas chambers in Auschwitz on August 9, 1942. Edith Stein died like this, in the words of some, sister Teresa blessed by the Cross.

She was beatified on May 1, 1987 and canonized on October 11, 1998 By Pope John Paul II.

Bibliography:

FABRETTI, Vittoria, A life for love, São Paulo, Paulinas, 1999.

KAWA, Elizabeth, Edith Stein, the blessed by the Cross, São Paulo, Quadrante, 1999.

MIRIBEL, Elizabeth de, Edith Stein. Like gold purified by fire,

Aparecida/SP, Santuario, 2001.

Www.ewtn.com/faith/edith_stein.htm

FABRETTI, Vittoria, A life for love, São Paulo, Paulinas, 1999.

KAWA, Elizabeth, Edith Stein, the blessed by the Cross, São Paulo, Quadrante, 1999.

MIRIBEL, Elizabeth de, Edith Stein. Like gold purified by fire,

Aparecida/SP, Santuario, 2001.

Www.ewtn.com/faith/edith_stein.htm

.png)

1 comment:

So beautiful! Thank you for sharing, Anna!

Post a Comment